Control: More or Less?

It’s hard to imagine that there can be any problem with exercising self-control. Isn’t willpower an essential aspect of being a high-functioning individual? Restraining our urges and impulses as well as focusing on long-term goals rather than giving in to instant satisfaction—what’s not to want about having more of that? But here’s the thing: Recent research has discovered that “more” does not always mean “better.” There can be just as many concerns with too much self-control as with too little exercise.

Do you remember the marshmallow study, where small children were tempted by marshmallows, and the ones who waited to eat them got more marshmallows? I can still see their tiny, contorted faces as they stared determinedly at a marshmallow trying to resist the urge to eat it immediately. Delayed gratification can be just as hard for adults as it is for children.

Inside the marshmallow study.

The marshmallow study initially began in 1960 at Stanford, where a psychologist named Walter Mischel offered children a choice between one marshmallow, which they could eat immediately, or two marshmallows, which they could eat 20 minutes later if they resisted the immediate urge. Years later, Mischel followed up with these same children and found that the kids who were able to delay their gratification in kindergarten did better on their SATs and had lower BMIs years later. As a result, marshmallow symbols began popping up on everything from T-shirts with the quote “Don’t eat the marshmallow” to retirement planning logos. It became a national symbol of self-control or delayed gratification.

I even heard one first-grade teacher discuss children by saying that there are two kinds of kids: “marshmallow eaters” and “marshmallow resisters.” Of course, from the teacher’s perspective, this makes the children “easier to manage in the classroom.” However, she was also making the point that kids who are able to resist marshmallows at age 6 would go on to choose vegetables over doughnuts later in life and have an overall healthier lifestyle, which supports Mischel’s earlier findings.

What the new research says.

A new study conducted by Dr. Liad Uziel of Bar-Ilan University’s Department of Psychology, published in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science, argues that there may be as much of a concern with too much self-control as exists when an individual has not enough.

“Examples include inflexible behavioral patterns, overemphasis on norm-adherence at the expense of personal discretion, and strict emphasis on cold and rational thinking while overlooking intuition and emotional inputs,” says Dr. Uziel. He goes on to say, “There are studies showing that it is challenging to maintain high self-control over time. Intensive self-regulatory efforts can lead to all sorts of problems, including health problems associated with intense stress.”

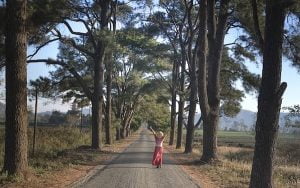

Exercising high levels of self-control can result in rigidity in our behavior, an emphasis on rational thinking to the exclusion of intuition. Sometimes, our spontaneity is the key to us staying fresh and creative. It can be in the moments when we let go of what we think “should happen” that we become more open to the possibilities of what “could happen.” The unplanned weekend away, the surprise love affair, the decision to take a day off work to be with an old friend can all be doorways to an exciting, new adventure and sources of unexpected creativity. When we do not leave ourselves open to these opportunities, we may close doors that we never knew existed.

Try emotional regulation instead.

Emotional regulation, or the ability to manage our stressful reactions to others, is an essential aspect of emotional intelligence, which is a key factor in successful relationships from our deepest intimates to our business colleagues. Anger, frustration, and jealousy—while all normal human feelings—can wreak havoc in our work environment and love lives when we don’t know how to channel those feelings and when we’re unable to stop ourselves from acting upon them.

Feeling immediate fury, for example, is not a sign that we should go into a rage with a co-worker who just used our data and accepted credit for the work. Rather, it should be a reminder for us to find a useful way to manage our emotions and responses to achieve our best. In each challenging situation, there is a lesson to be learned from it if we can stay calm enough to look for it.

Therapy to help with excessive self-control.

There is a type of therapy called Radically Open Dialectical Behavior Therapy (RO DBT), which theorizes that excessive self-control can be problematic for some people. The symptoms manifest in people feeling “over-controlled” and inclined to mask their true feelings. These people tend to focus on details rather than seeing the larger picture and are highly perfectionistic. They may appear aloof and distant in their interactions with others. While excessive willpower and self-control can be functional at times, it can also come at a high cost by leading to depression, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and being seen by others as cool and emotionally unavailable. RO DBT helps people become more fluid, spontaneous, and accepting of the human condition as imperfect as we all are.

Self-control is a tool, and an important one at that. Like most things in life, both overuse and underuse of it can be harmful. To live our best lives, we need the strength and gifts that exercising self-control brings and the wisdom of knowing when to apply it and when to let it go so that we can be a version of ourselves that we’re proud of.

This post originally appeared in MindBodyGreen.